This blog, for obvious reasons as you progress, is not to explicitly advocate or encourage (or discourage) adults to engage in the act of guerrilla playwork, but rather, to explain what it is, and why some adults choose to do it!

Pictured Above: The tree pictured here resides in a green belt running alongside a train line. On occasion, pallets and other resources appear and the local kids get stuck into some awesome tree house making. These are usually removed at some point by higher authorities only to reappear a few months later.

What Is Guerrilla Playwork?

Guerrilla playwork is a grassroots, often spontaneous approach to creating play opportunities for children in spaces not traditionally designed for play.

Borrowing the word “guerrilla” from unconventional, small-scale activism, guerrilla playwork is about:

Acting quickly and creatively

Using available materials

Reclaiming overlooked or underused spaces

Prioritising children’s right to play

It is not about recklessness or confrontation. Rather, it is about quietly disrupting adult control of space in order to make room for children’s agency, imagination, and experimentation.

At its heart, guerrilla playwork is deeply aligned with the principles of the UK playwork movement and the concept of the playwork intervention style, where adults seek to remove barriers to play rather than direct it. It echoes the ethos seen in adventure playground traditions and “loose parts” theory — where the environment, not instruction, fuels creativity.

Pictured Above: The beautiful simplicity of a sink appearing in a green space… (Photo Credit Monique Goodwin)

Guerrilla playwork might look like:

Dropping off tyres, pallets, and fabric in a vacant lot

Closing a street temporarily for free play

Setting up a pop-up mud kitchen in a park

Releasing chalk, crates, and rope into an unused concrete space

Transforming a sterile courtyard into a temporary adventure zone

Pictured Above: Simply by providing resources in a space has led to magic… (Photo Credit: Renae Powell)

It is temporary. It is adaptive. It is responsive. And it is often slightly subversive.

What Does It Mean Philosophically?

Guerrilla playwork carries several deeper meanings:

1. Children Are Citizens Now

It asserts that children do not need to wait for purpose-built playgrounds or adult permission to experience rich play. Public space belongs to them too.

2. Play Is Not a Program

It resists over-programmed childhoods filled with adult-designed outcomes. Guerrilla playwork privileges process over product.

3. Risk Is Not the Enemy

It challenges risk-averse cultures that sterilise childhood. Instead, it trusts children’s competence.

4. The Environment Is the Third Teacher

Drawing loosely on ideas from educational philosophies like those associated with Malaguzzi, guerrilla playwork treats space and materials as catalysts for creativity rather than backdrops.

Why Would Someone Engage in Guerrilla Playwork?

There are practical, political, and philosophical reasons.

1. Because Children Are Losing Play Space

Urban densification, traffic, liability fears, and screen culture have drastically reduced children’s independent outdoor play. Guerrilla playwork becomes a form of advocacy in action.

Instead of writing submissions or waiting for funding, it says:

“Let’s make something happen — now.”

Pictured Above: Swings are one of the simplest and very effective acts of guerilla playwork… (Photo Credit Monique Goodwin)

2. Because It Builds Community

Pop-up play changes how neighbours interact. Adults pause. Conversations begin. Children of different ages mix. Informal supervision emerges naturally.

What was once an empty space becomes a social hub.

3. Because It Restores Agency

Children who are constantly managed often become passive. When loose parts appear in an unstructured environment, something shifts:

They negotiate.

They invent.

They solve problems.

They take ownership.

Guerrilla playwork says: We trust you.

Pictured Above: The pruning of an opening in a bush, and the addition of resources and presto…

4. Because It Models Courage

For playworkers, educators, and community members, engaging in guerrilla playwork is also about modelling:

Creative defiance

Ethical disruption

Advocacy through action

It demonstrates that meaningful change does not always begin with policy. Sometimes it begins with a milk crate and a patch of dirt.

Pictured Above: Simple. Simple. Simple. Yet absolutely the relics of authentic fun. (Photo Credit Renae Powell).

Is It Legal? Is It Responsible?

Guerrilla playwork sits in an interesting space.

It is not inherently illegal — but it can push boundaries around permission, insurance, and formal approval. Responsible guerrilla playwork still considers:

Safety without eliminating challenge

Respect for property

Leaving spaces as good or better than found

Community relationships

It is not chaos. It is intentional informality.

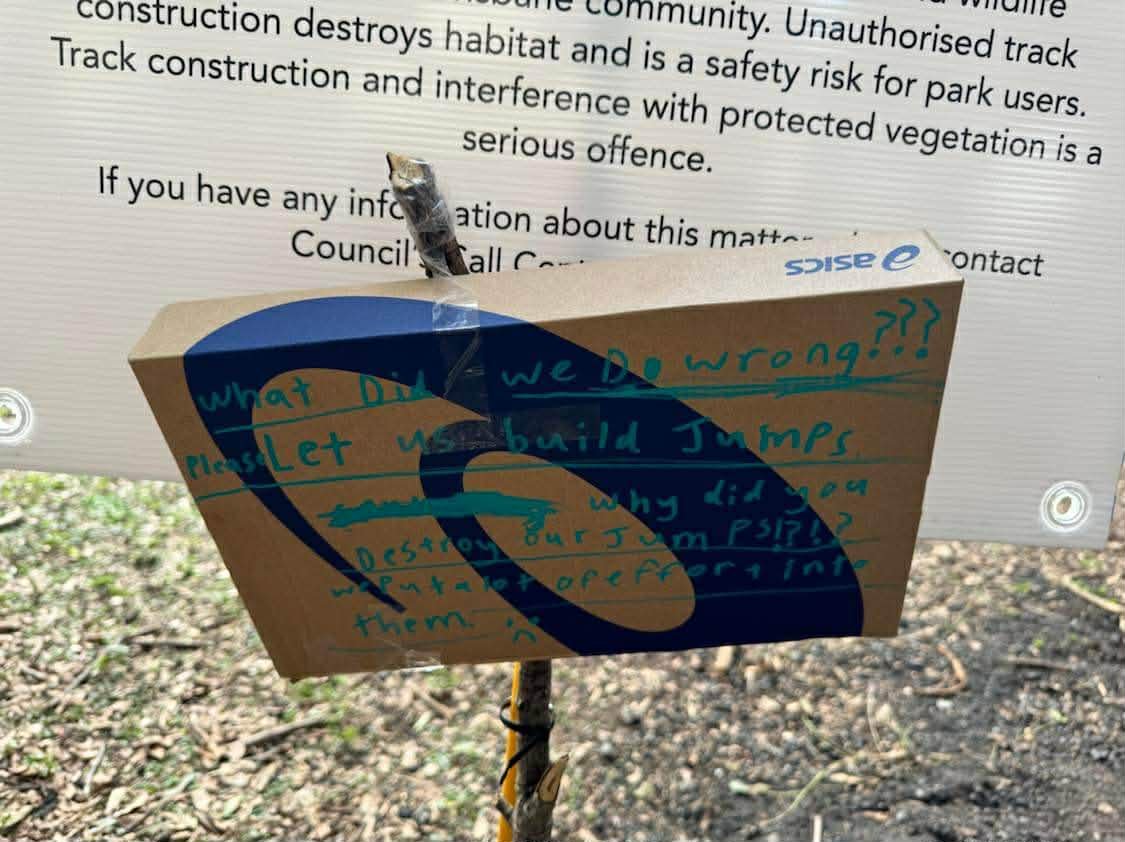

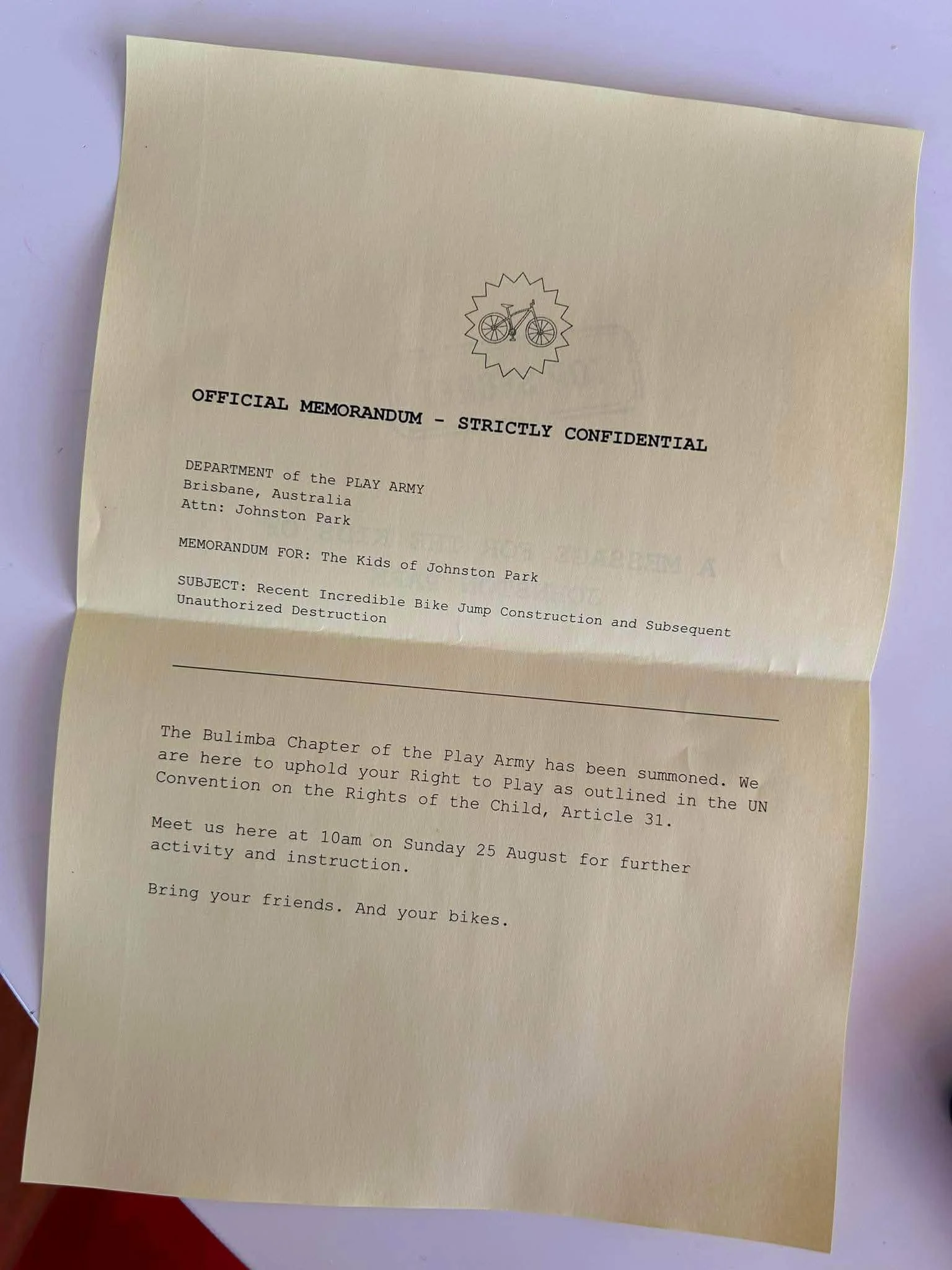

Pictured Above: The first picture shows a challenge from local children after their play was impeded. The second two shows a guerilla playwork intervention in action which resulted a large community day of play in the park!

A Final Thought

If traditional playwork is about creating environments where play can flourish, guerrilla playwork is about creating those environments where they don’t yet exist.

It is hopeful.

It is practical.

It is slightly rebellious.

And in a world increasingly designed for efficiency and surveillance, it is a radical act of trust in children.

Angus Gorrie