On Monday the 24th January 2023 there was great news for the playwork sector of Australia… The release of the updated and revised framework for school aged care, My Time Our Place (MTOP). The original MTOP document was a first of its kind for school age care in Australia, a significant deal at the time firmly establishing the OSHC sector as different from, and as important as early years education. However the document was dated and it was with much excitement that the sector itself was engaged to contribute to this revision, the very sector that had been using it, engaging with it, and understanding the benefits of the challenges. As part of that engagement, numerous “playworkers” threw their hats in the ring and contributed their thoughts, several of these making there way into the new publication.

First and probably most obvious to all those that have perused the document is a very deliberate and proud inclusion of the term “Playwork” in the glossary (DEEWR, 2022, p. 67). Now, not only is this exciting as it is the first time playwork has been legitimised as a legitimate way of working with children in the OSHC (or any other) sector in Australia… But the definition itself is quite sensational.

(DEEWR, 2022, p. 67)

As a playworker working within an OSHC setting there are aspects of this definition worth unpacking. First of all, the significance of the word “affective”. Much too many university assignment markers dismay “affective” and “effective” can sometimes be used interchangeably in our vernacular much to the detriment of the actual meaning. When we are affecting the environment, we are dealing with inceptions, birth places and beginnings. This is an excellent thought to ponder for the outcomes or “effects” focussed educators. As a playworker this is music to my ears as this allows more thought towards creating spaces and supporting practice that leads to infinite games and possibilities, rather than planning a finite, desired outcome. The unpredictability of this “affective” approach has in the past caused conundrum for OSHC educators in how they explain their application of the framework to accessors… Now, the explanation is embedded in the Framework!

Furthermore in the definition of playwork comes the suggestion of “affecting the whole environment”. This lends itself to the notion that practice starts well before children are even present, and the “affordance” of space and the various “play cues” a space projects are considerations that are important ones for an OSHC educator to consider. These ideas also lend a helping hand (potentially) for educators advocating for their spaces within a school to stakeholder (school faculty, P&Cs, education department). Affective spaces can be seen not as niceties to be begged for by the playwork inspired, but rather necessary for OSHC practitioners to deliver the Framework. Last but not least this creation of affective environments is described to improve opportunities to play. Not for play and learning. Not for play and leisure. Not for play and physical development. Play for plays sake has been given its appropriate place in the national framework for school age care in Australia and that’s a milestone!

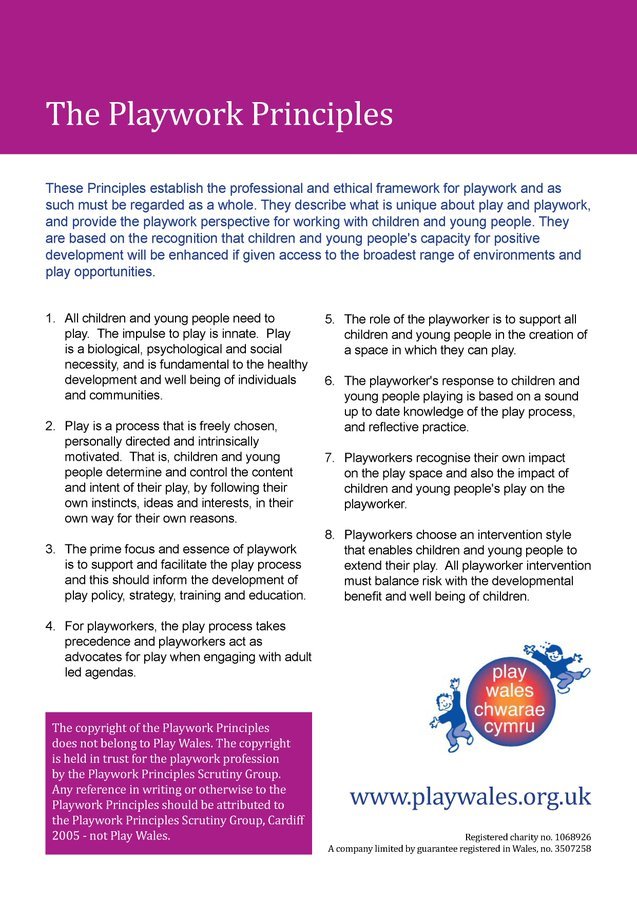

Another significant aspect of change between MTOP 2011 and MTOP 2022 is the increase in the understanding of risk as it presents in play. In fact, not only has the word count for risk gone from 3 to 12 between documents, but the specific term “risky play” gets a mention, and even more interestingly as an outcome for children having a strong sense of wellbeing (DEEWR, 2022, p. 51). This is powerful as risk is often shunned and relegated to the world of physical risk, despite most risk children engage in being social and emotional. Although the previous framework did mention risk, it was not specific to play where children can learn to tackle risk by first being able to detect it, make active decisions it, overcome it, all a self-motivated way. This is not to suggest educators in Australia become flippant with the idea of risk and its provision but we can lean further into playwork practice on this… Consider Playwork Principle No 8 (PPSG, 2015):

8: Playworkers choose an intervention style that enables children and young people to extend their play. All playworker intervention must balance risk with the developmental benefit and well-being of children.

Thus, the often championed but rarely official tools of “Risk Benefit Assessment”, and “Dynamic Risk Assessment” now become highly relevant to Australian educators in the delivery of the framework. Another huge stride for playworkers in OSHC settings who have been applying these approaches for a while.

Deeper down the rabbit hole of playwork specific theory and practice we can also see the inclusion in the glossary of the Play Types (DEEWR, 2022, p. 67).

One of the first academics in the playwork realm, the late Bob Hughes is responsible to the citation of this inclusion and it should get some thought provoking critical reflection going amongst teams (Hughes, 2002). Many of the play types can challenge educators in all settings for a variety of reasons. Perception around play types such as rough and tumble play for example often elicits great debate, usually emotive without applying a critical reflection and evidence to the potential benefits. Deep play is another than cause a stir, the definition being:

“Play which allows the child to encounter risky or even potentially life threatening experiences, to develop survival skills and conquer fear. This type of play is defined by play behaviour that can also be classed as risky or adventurous”. (Hughes, 2002)

The inclusion of the play types is rather ground breaking as it encourages educators to see play as far more than smiling happy games. Play can involve conflict, adversity, challenges and so it should, as it is ideal that children should engage with these emotions in play when the stakes are low, rather than in real life when they are high. What this also allows us to do is throw out the window the idea of “good play” or “bad play” on focus on the play that just “is”. If we as a sector can do that, and appreciate that despite perception there may a function to this play type, we can understand and support play better and more broadly.

Without going down an absolute rabbit hole for a short blog piece (you will need to read up on Haekel (1901), Hall (1904) and Reaney (1916) to learn more), the separation of “Recapitulative Play” from the 16 into its own definition of the glossary is also interesting and likely to create much discussion and reflection. While the definition in the MTOP 2022 (p. 68) is descriptive, an unpacking of the deeper theory will break it down into the categories: animal, savage, nomad, pastoral and tribal, will take some in depth understanding of the older biological theories of play, especially as recapitulative play appears as a suggested outcome in Outcome Two: Children and young people are connected with and contribute to their world (DEEWR, 2022, p. 45).

Last, but certainly not least is a subtle easter egg that would be easy to miss unless you are a vocational playworker or playwork inspired. In MTOP 2022, play itself gets a definition in the glossary which in itself is significant being that MTOP 2011 only defined “play based learning” in its glossary. But the definition may be familiar to some of you…

While being an entirely apt definition itself, especially proposing that play is not a nicety, a fun thing to squeeze in between the important stuff, but rather FUNDAMENTAL to individuals and communities, the playwork origins of this definition come straight from the Playwork Principles themselves… Playwork principle No 1 and 2 state:

1: All children and young people need to play. The impulse to play is innate. Play is a biological, psychological and social necessity, and is fundamental to the healthy development and wellbeing of individuals and communities.

2:Play is a process that is freely chosen, personally directed and intrinsically motivated. That is, children and young people determine and control the content and intent of their play, by following their own instincts, ideas and interests, in their own way for their own reasons.

I am sure it is not hard to trace the lineage of our new Australian MTOP 2022 definition.

Overall, it will honestly be interesting to see what happens next for playwork in Australia in a school age care context. This new framework is presently being cheered by many already playwork inspired educators in Australia and has already, if our emails are to be intercepted correctly, causing a new wave of curiosity. However… Will it be supported, can deep running perception be overcome, will communities support a move to this delivery of care for children? I would suggest that these are questions are the same ones that float around in the playwork community universally and always have and it is into that larger global community we will be able to lean on to glean some insight.

From an OSHC context, if there are any practical or theoretical aspects of getting started in playwork you would like to discuss… Just reach out!

Regards

Angus Gorrie

DEEWR. (2011). My time, our place: Framework for school age care in Australia. Canberra : Commonwealth of Australia.

DEEWR. (2022). My Time Our Place: Framework for school age care in Australia V2.

Haekel, E. (1901). The Riddle of the Universe at the Close of the nineteeth century. London: Watts & Co.

Hall, S. (1904). Adolescence: Its psychology and its relations to physiology, anthropology, sociology, sex, crime, religion, and education. New York: Appleton.

Hughes, B. (2002). A Playworker's Taxonomy of Play Types (2nd ed.). London: Playlink.

PPSG. (2015). The Playwork Priciples. In The Playwork Principles Scrutiny Group. Cardiff.

Reaney, M. J. (1916). The Psychology of the Organised Game. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.