As a playworker and play advocate one of the more frustrating things can be convincing stakeholders that play is worth talking about in the first place. This comes across very pessimistic granted, largely as this blog is being written by a playworker having melancholic musings on the back end of a break going back onto the working year! However, at the very least, even in spaces where play is seen as “necessary”, it can still be discussed as “the thing” that happens around the important stuff, as opposed to something critical in its own right.

Often, to slide more play into the school day it is harnessed as learning in its own right. “Play Based Learning” for example is something every reader would no doubt have heard about despite the many understandings about what this actually means. The risk, and one evidenced all to often is this leading to learning and activities being dressed up as play, but lacking any authentic self-directed or intrinsically motivated aspects.

For the purpose of “justifying” more play in school and care settings, this blog will ask you toy with, as opposed to “play based learning” a different term… “Play for learning”…

What “Play for learning” allows us to do is leave the play alone! Allow it to be play for plays sake, play in its own right, play that is freely chosen, personally directed and intrinsically motivated. However, because we are, (most of the time), a highly intelligent species we can also appreciate that science and development do not happen in bubbles of isolation. We are an evolutionary Venn diagram of cause and effect and every action has a reaction…

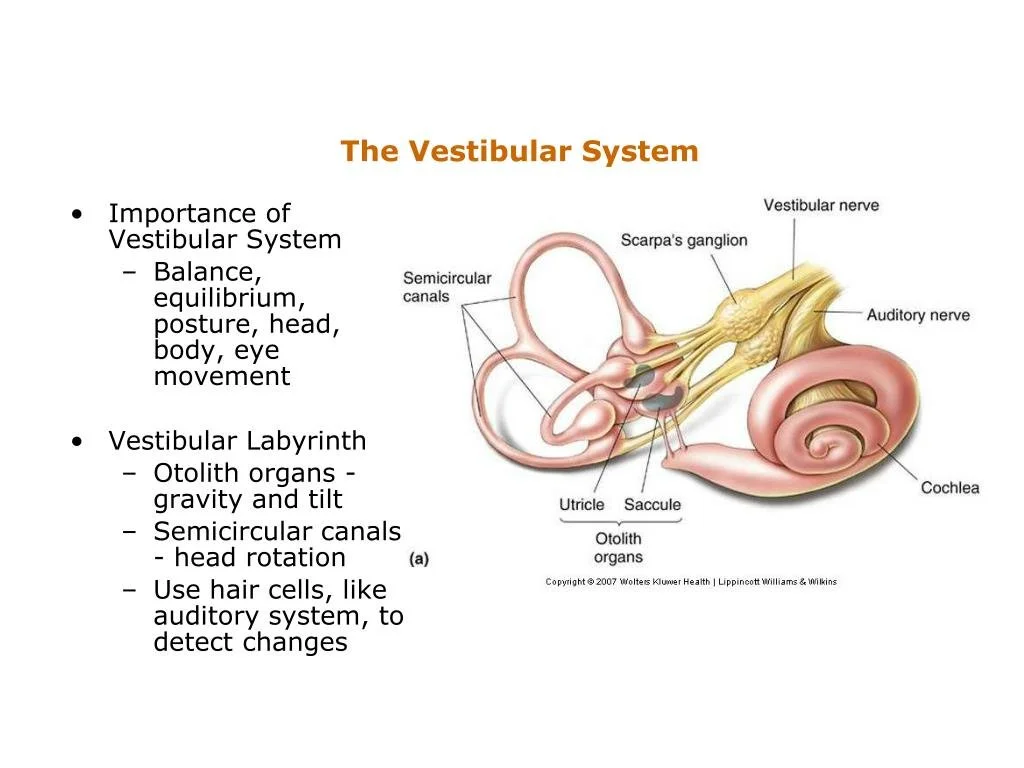

Take for example the need for us to develop, test, refine our vestibular systems… How one does this, and why this is so critical for the life of a “school student”…

Engaging your vestibular system in a loose parts playground happens naturally through movement, experimentation, and intrinsically motivated play. The vestibular system—located in the inner ear—helps with balance, spatial orientation, coordination, and body awareness. Loose parts playgrounds are especially powerful because they invite open-ended movement rather than prescribing how the body should move (as even the best teacher or playworker out there would be at a loss to understand what subtle and nuanced aspect of bodily development each and every child under their watch requires).

Here’s how it shows up in practice:

Climbing and balancing on crates, logs, tires, planks, or rocks challenges children to adjust their posture and center of gravity.

Spinning, rolling, and swinging with ropes, barrels, or suspended elements stimulates the inner ear and supports balance control.

Jumping, hopping, and stepping across uneven or movable surfaces strengthens spatial awareness and motor planning.

Building and rearranging structures requires children to move their bodies in different planes—bending, reaching, lifting, and crawling.

Risk-taking at a self-chosen level (e.g., deciding how high to climb or how fast to move) helps children learn to regulate their bodies and emotions.

Because loose parts play is child-directed, children instinctively seek the level of vestibular input they need (this is such a crucial point of difference between PLAY vs. ACTIVITIES dressed up as play)—whether calming (slow rocking, gentle balance) or alerting (fast spinning, climbing high, jumping and impact on surfaces). This supports not only physical development, but also focus, confidence, and emotional regulation.

A deficit in vestibular development can affect far more than balance as the vestibular system supports posture, movement, attention, and emotional regulation, delays or under-development can show up across many areas of a child’s life, including (bom bom bom!!!!)… The classroom.

Possible risks and impacts of vestibular development deficits

Physical and motor challenges

Poor balance and frequent falling

Difficulty with climbing, jumping, or navigating uneven surfaces

Delayed gross motor milestones

Low muscle tone or poor postural control

Trouble coordinating both sides of the body

Learning and classroom impacts

Difficulty sitting upright or remaining seated

Fatigue during desk work due to poor core stability

Problems with eye tracking and reading (the vestibular system supports visual stability)

Reduced focus and attention, especially in sedentary tasks

Avoidance of physical activities

Sensory processing and regulation

Over- or under-responsiveness to movement (fearful of swings/heights or constantly seeking motion)

Motion sickness or dizziness

Difficulty regulating arousal levels (appearing overly active or lethargic)

Emotional and social effects

Increased anxiety, especially around movement or risk-taking

Low confidence in physical abilities

Withdrawal from peer play that involves movement

Frustration or emotional dysregulation when tasks feel physically demanding

Everyday functional skills

Difficulty with dressing (balancing on one foot, coordinating movements)

Challenges navigating stairs or crowded spaces

Poor spatial awareness, leading to bumping into objects or people

Why movement-rich environments matter…

When children lack opportunities for varied, self-directed movement—such as climbing, spinning, balancing, and rough-and-tumble play—the vestibular system may not receive enough input to mature optimally. Overly restrictive, sedentary, or overly “safe” play environments can unintentionally contribute to these gaps.

Loose parts playgrounds and nature-based play spaces help reduce this risk by offering:

Diverse movement experiences

Adjustable levels of challenge

Opportunities for repetition and mastery

Safe exploration of risk

The big trick here is to not see loose parts playgrounds as a fad, or a tick box but a space requiring professional skills and understandings to support well.

So… Let us kick the year off well with some real thought on your physical spaces, how often and for how long children can engage with them, and how freely they can do it! Let us see that PLAY is not a nice little thing that happens in isolation… If affects EVERYTHING… Let us ensure that the affect is a positive one…

Angus Gorrie